A premise of Wolfgang Ernst’s “Cultural Archive versus Technomathematical Storage” is that Jacques Derrida’s work on “archive fever” lends itself to a reflection on “archival e-motion” (53). Ernst insists that the archive, in the traditional sense, is not dynamic by itself; rather, it preserves motion by spatializing it (55). This being said, the electronically pulsed archive and, more recently, the digital archive (which correlate—but are not exactly compatible—with dynamic or network memory, instant processing, unlimited storage, and the subjectivization of archiving) bring, along with the interface, a new dynamism that signals a fluctuation in the very logics of calculation and organization that shape the archive (53-7).

For Derrida, the archive is made possible by a death, aggression, or destruction drive that emerges as both the finitude of institution or command and the infinity of a movement that yields archive desire and fever (4, 17, 94-5). In light of Derrida’s idea that the archive, despite its containment, is “entrusted to the outside” (12), I propose that the archive’s dynamism is not as hermetic as Ernst suggests. The archive—electronic or not—is an impetus in itself, insofar as it participates in a nexus of desire and possesses a capacity to affect (or change, touch, move) me as much as I can affect it. The performative archive, Eivind Røssaak’s phrase for “collections that do something” (1; emphasis in the original), magnifies or accelerates the process whereby the archive conveys a force (Derrida’s term: 7, 12) beyond its boundaries.

The archive’s capacity to move beyond itself is obvious in the English title that was ascribed to Derrida’s book. Fever implies heat, agitation, and contagion.[i] In French, le mal d’archive has a slightly different connotation. It indicates a malaise, a longing—both a desire and an extension or elongation. In brief, the English translation employs the language of virality, whereas the French term more overtly evokes Derrida’s concept of “trace” (20). Whether it is through contamination or through the accumulation of residues, though, it is clear that the archive travels.

Neither footnotes nor index cards (to echo Peter Krapp on the topic of hypertextuality), here are some examples of archives that move beyond themselves via material and affective networks:

- Durba Ghosh, “National Narratives and the Politics of Miscegenation: Britain and India” (2005)

When retracing the partly repressed history of miscegenation in India, Ghosh discovers that investigating the interstices of colonial archives can provoke discomfort and contempt both in the present and within cultural contexts exceeding the audiences for which the documents were originally destined. - Joseph Masco, “As We May Think, 2012” (2013)

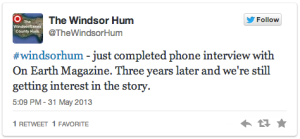

“As We May Think, 2012” is a contemporary take on Vannevar Bush’ 1945 homonymous essay (see Ernst 62). Bush’s paper haunts Masco’s project and has potent contemporary repercussions. - @TheWindsorHum, The Windsor Hum (2011-today)

If the Internet is not an archive, as Erst argues (64), the Twitter account of anonymous user(s) @TheWindsorHum presents a chronologically ordered narrative that makes it “properly archival.” In this interactive archive (see Røssaak 9-10), tweets convey, in 140 characters or less, the alienation of noise pollution on the East shore of the Detroit River. The sheer accumulation of negative affects through text is hypnotizing.

My addendum to Ernst’s research, then, is twofold. First, the motion that Erst observes in the electronic archive operates amidst material and affective networks that permit the archive to move across time and space. Second, as the example of Ghosh’s anthropological research demonstrates, the (affective) dynamics in which the archive partakes are not specific to non-state, electronic, or digital archives; however, the performative archive perhaps intensifies or dramatizes said dynamics.

Works Cited

- Derrida, Jacques. Archive Fever: A Freudian Impression. Trans. Eric Prenowitz. Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1996.

- Ernst, Wolfgang. “Cultural Archive versus Technomathematical Storage.” The Archive in Motion. Ed. Eivind Røssaak. Oslo: Novus Press, 2010. 53-73.

- Ghosh, Durba. “National Narratives and the Politics of Miscegenation: Britain and India.” Archive Stories: Facts, Fictions, and the Writing of History. Ed. Antoinette Burton. Durham: Duke University Press, 2005. 27-44.

- Masco, Joseph. “As We May Think, 2012.” Social Text Periscope (2013): n. page. Web. 2 October 2013.

- Røssaak, Eivind. “The Performative Archive: Art, Technology, and New Media.” 2011. Conference paper.

- The Windsor Hum (@TheWindsorHum). Twitter. 2011. Web. 2 October 2013.

[i] Fever is also a manifestation of auto-immunity: the body reacts to the infiltration of an external threat by producing heat, inasmuch as the body becomes in excess of itself.

I’m especially interested in the final part of your post, Jean-Thomas, which raises many interesting questions. As you suggest, the affective, mobile, and performative dimensions of an archive are surely not specific to digital archives. How, then, do we mark the difference among print and digital archives? What do such distinctions get us and do they remain merely heuristic? Do digital archives merely intensify dynamics that are present in all archives? Does the raw quantity of internet archives and the challenges they pose to individual human cognition represent a change not merely in degree but in type (e.g., with 100 hours of video being uploaded to YouTube every minute)? If the current web exists on a spectrum with print archives, might we imagine a future configuration that is truly an anti-archive? Is this what we get with Ernst’s suggestion of “cloud modeling” and its oscillation among macro and micro levels, including “multirate time integration, time stepping and massive parallelization as key for numerical computations” (“Cultural Archive versus Technomathematical Storage” 70)?

Thank you for the very helpful questions, Patrick. While some of the issues you’re raising will require further reflection on my part, I thought I’d jot down a few thoughts and–why not–add to the pool of questions already being considered.

Let me start with an addendum to my previous addendum (!): While all archives move beyond themselves by virtue of having the ontological capacity to affect and be affected, this movement is not consistent across media or locales. In other words, while both print and digital archives affect, they do so in different ways. If my reading is correct, your proposition that the electronic or digital archive constitutes a change both in scale *and* in type is consistent with Deleuze and Guattari’s definition of assemblage as an “increase in the dimensions of a multiplicity that necessarily changes in nature as it expands its connections” (A Thousand Plateaus 8). If Ernst is right that the notions of archive and storage have evolved somewhat in relation to each other, it becomes clear that the print archive must be different in nature from the digital archive because the latter’s telos is to order not something that is large, but instead something that is virtually infinite.

Now, where do we draw the line between print and digital archives? I’m not sure we can, especially in light of N. Katherine Hayles’ assertion that in “the contemporary era, both print and electronic texts are deeply interpenetrated by code” (“Electronic Literature: What Is It?”). If we want to pose the question as a historical one and inquire into the cognitive and bodily transformations that have accompanied the experience of a quantitatively and qualitatively “morphed” archive, our task would be, I think, to track the role of the technical and the technological in human ontogenesis–something that reminds me of Gilbert Simondon’s writings on individuation (http://goo.gl/lGSBxm). I believe that John Protevi’s book on affect as the connection between the social and the somatic (http://goo.gl/sjvAR3) as well as Patricia Clough’s work on auto-affection in the age of teletechnology (http://goo.gl/AeY6PZ) would be pertinent to such a project. I don’t want to reduce this comment to a mere exercise in name dropping; what I’m hoping to do is grasp the theoretical implications of mapping out the change in type induced by an assemblage’s change in magnitude.